12 Top Tools for Competitive Intelligence

A good competitor research project will use many sources to collect as much information as possible about the target competitor. The two main categories of information for competitor analysis are:

Primary fieldwork (let’s think of that as telephone calls similar to traditional market research) – this is sometimes called humint, meaning human intelligence

Public sources of information, mainly available online – this is sometimes called osint, for open source intelligence (but includes sources that may charge for such information)

This article is about the public sources of information.

We use hundreds of public sources across the many competitive research projects that we conduct, but most of the useful information in any one project comes from only a handful of sources, and it’s usually the same sources. Below are the public sources of information that we use most frequently. Almost every competitor analysis relies on all of the sources below to some extent.

Before we talk about each source, this table shows what type of information each source is good for.

1. Competitor websites

As a source of information, competitor websites can be hit and miss. Most of what they say may seem like soft marketing content, but they can provide highly relevant information:

Competitor Pricing: Software companies often provide some indication pricing on their website. This is mostly the case if they target consumers or small businesses. It is rare for them to provide enterprise pricing, but you may be able to extrapolate roughly from the pricing offered to smaller businesses.

Employees: Competitor websites may describe the leadership team, from which you may get a sense of the corporate structure and how that may influence the company’s strategy. Case studies will also feature employees, with clues as to what kind of roles help to sell or implement the products.

Marketing: If nothing else, websites have plenty of information about competitor’s messaging. How do they present themselves? Do they talk about features or benefits? Does a focus on features suggest a productized offering or does talk of solutions suggest a service offering? What industries do they address? What use cases? And so on.

Product: Competitor websites should be the first port of call for understanding their product. Sure, the product may be described only at a high level, but it is an easy place to start. How the competitor talks about their product

Customers: companies typically list key customers and provide case studies. Customer names can tell you something about the competitor’s target segments, for example enterprise vs small business, or the industries in which they are most successful. Case studies may have information about the sales process or post-sales services. In both cases, the job titles of buyers or users will shine a light on the kind of role that the competitor targets.

Even if it turns out that a competitor’s website does not give you some of the above highly useful information, you can’t not check – just imagine the loss of credibility if you analyze a competitor and your audience found out you had not checked the competitor’s website. Even worse, if something that you had been unable to find, turned out to be on that competitor’s website.

2. Annual reports

Again for public companies in the US, no competitor analysis is complete without reading the company’s quarterly and annual reports. At the very least, read their annual report, but reading the last year’s worth of quarterly reports is also useful. ‘Last year’ will probably mean Q1, Q2 and Q3 as the Q4 report is usually rolled into the annual report. The best source for annual reports is the SEC website.

Financial reports are the definitive source of financial information, including revenue and expenditure, sometimes with product and geographical breakouts. They also often provide customer numbers (which alongside revenue information, gives some clue about pricing), detailed explanations of their corporate and product structure (which often differs from how their website is structured). Annual reports tend to list whom they consider their most important competitors, so it can be enlightening to see if you feature on that list.

Some aspects of reading an annual report involve taking calculated gambles on what the information means. For example, if a competitor lists multiple product areas in a qualitative discussion of its business, can you assume they are in descending order of revenue? Sometimes, competitor analysis does mean making such half-guesses, which may be informed by information from other sources.

Reading older annual reports can also be useful in competitor research. While most of the useful information will be in the most recent report, changes across reports can be meaningful. For example, a competitor may only break out countries outside the US if they contribute more than ten percent of revenue. This year, that may be no countries but two years ago, the UK may have been such a contributor, giving you some sense of the UK’s contribution even today.

A small number of non-public companies also publish reports similar to annual reports, in an effort to be more credible, including foreign companies not legally obliged to file but wanting to give US audiences more transparency.

Examples: SEC search, Annual Reports

3. Earnings calls

For public companies, earnings calls are almost a mandatory resource in competitive intelligence. They are filled with nuance and additional detail behind the quarterly or annual reports. A great source of transcripts is Seeking Alpha.

Executives may mention big wins, or address future strategy, or talk about recent product launches, in a way that they rarely do in the financial reports. Some companies use earnings calls to provide further breakout of numbers, or address their performance by geography, or give additional detail on expenditure.

Reading between the lines may also let you derive some conclusions from what the company doesn’t say on the call, or the analyst questions that they try to avoid answering. Although this involves guesswork as much as anything else.

Read through (or listen to) the last four quarters of earnings calls transcripts as a minimum, and if time allows, the last eight quarters. Reading the last eight quarters of transcripts may show you how the competitor’s focus has changed over the recent past – for example, some category of information that they used to share and no longer do may point to a downturn in that business, or a category that they only recently started sharing may point to a growing business (for example calling out business divisions when they reach $1B even though they don’t explicitly announce that revenue milestone).

Examples: Seeking Alpha, Yahoo.

4. Wayback Machine

The Internet Archive, also called the Wayback Machine, stores snapshots of websites on a regular basis. So you can see how a web page changed over time, which is useful in multiple ways.

Seeing how the text on a web page, or the navigation menus of a website, have changed over time provides clues as to a company’s changing focus. It can also tell you when new products were introduced, or made more/less prominent. And likewise for new industries or use cases.

Most satisfyingly, older copies of a website may feature pricing information that has been removed as the company grew. Or if pricing pages do feature on the current website, older copies of that page may contain more complete information. To find old pricing pages, you can find older versions of the website and check the navigation menus, or if you get lucky, try competitor.com/pricing (the most common URL used for pricing pages) and see if there are snapshots of that page.

5. BuiltWith (and similar)

A number of websites provide lists of the technology stacks used by companies. Mostly these are built from code found on those companies’ websites, so they lean towards external-facing software such as CRM, ecommerce and web technologies, but they also may draw conclusions from customer lists and other sources to identify technologies used internally.

Conversely, because for example they identify a thousand specific websites using Tech Vendor X, they then know a thousand customers of Tech Vendor X, and the market penetration of Tech Vendor X because they also know how many companies do not use that technology. So these websites are a good source of customer lists. These customer lists can run into the millions of customers for popular technologies such as Google Ads, with the ability to filter by geography, size and other criteria.

Examples: Builtwith, Similarweb, NerdyData, PublicWWW.

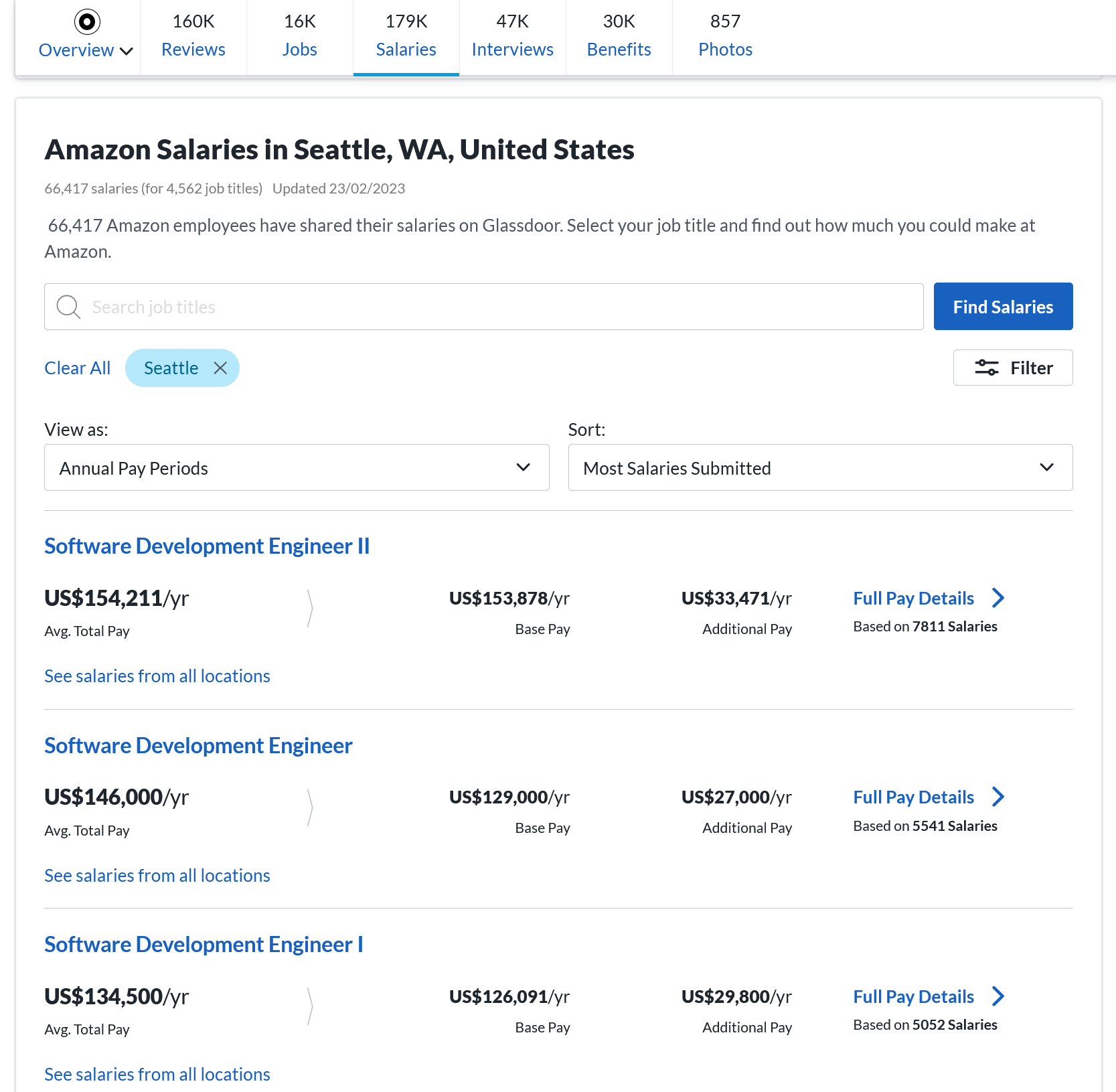

6. Glassdoor (and similar)

Glassdoor is primarily known as a source of employee reviews about their employers, but that is of limited value for competitor research. Partly because there are limited insights that you can draw from that information, and partly because most reviews are uninformative and lean towards general gripes about how management promotes the wrong people.

But Glassdoor also provides compensation information with breakouts for salaries, commissions, bonus and stock. This is useful in competitor analysis, certainly where the focus is on hiring vs. a competitor but also in understanding in what areas the competitor is investing.

Glassdoor is not the only such source, although perhaps the one with the best breakout of compensation into elements such as salary and stock. Others are listed as examples below.

Examples: Glassdoor, CareerBuilder, PayScale, Salary.com, Levels,

7. LinkedIn

LinkedIn is an excellent source of competitor information for several purposes:

Headcount: LinkedIn provides headcount for companies but also for functional units such as sales, marketing, operations, consulting and so on. These are approximations but they are good enough for most analysis. Headcount can also be filtered by geography and seniority. Headcount by geography is useful not only to identify which geographies are most important to the competitor, but in which areas they have any presence at all, and whether they offshore some of their headcount. Headcount may also give you an approximation of revenue if you make assumptions about typical revenue per headcount of your competitors, perhaps based on your own company’s revenue per headcount.

Employee names: most obviously, LinkedIn provides the names of employees, including key leaders. You can filter by seniority, for example narrowing down the list of names to just SVPs, and by functional areas and geographies, so you can identify Account Managers in California, say.

Roles: Competitor employees can be filtered by role, such as Marketing Director, Security Engineer or Head of Professional Services. This will give you some sense of the competitor’s areas of focus, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of their capabilities.

Sales targets: The text of individual profiles can yield useful information, and sales numbers is one such area. Salespeople will sometimes list their targets, or their achieved sales revenue. This may mean reading through hundreds of profiles of salespeople, but the results can be worth the effort. And reading these profiles can uncover other information, such as sales territories or key clients. Less directly, the profiles of sales employees may reveal whether salespeople sell individual products or combinations of them, the weighting between farming and hunting, the structure of sales teams, the role of post-sales services, and a raft of other information.

Areas of responsibility: senior employees commonly describe the teams that they manage and their areas of responsibility, allowing you to understand how a competitor is structured, how they go to market and how different functional areas interact with each other.

Growth: For companies other than the very smallest, LinkedIn will show a graph of headcount over the past two years, which you may be able to use as a proxy for revenue growth or the company’s expectation of growth.

Customers: one way to find a competitor’s customers on LinkedIn is to read the profiles of the competitor’s salespeople, who many mention customers that they manage. Another is to search for profiles outside of the competitor, that mention the competitor’s products – these may be people who use those products, almost certainly identifying their employer as one of the competitor’s customers.

LinkedIn is a good enough tool for competitive intelligence that we recommend paying for one of the advanced tiers that offers advanced search capabilities.

8. Crunchbase (and similar)

Crunchbase is a good source of information about the funding rounds of competitor startups. Crunchbase will tell you whether a competitor has raised money recently, and how much. Alongside other data such as growth data from LinkedIn, and revenue data based on LinkedIn headcount, and assumptions about profitability based on the company’s maturity, that may give you clues as to the competitor’s financial soundness.

Examples: Crunchbase, Inc5000, Latka, Privco.

9. Google

Unsurprisingly, every competitor analysis project relies heavily on Google. Just as a matter of routine, searching for the competitor’s name alongside search terms such as ‘revenue’, ‘launch’, ‘acquisition’, ‘strategy’ and other such terms will provide helpful information. Work your way through the first hundred or so results (setting Google to show you 100 results per page will bypass the tediousness of clicking through ten pages of only ten results per page). Let serendipity be your guide.

Other useful searches can be for filetypes (e.g. “competitor case study filetype:pdf”). Once upon a time, searching for xlsx files could deliver gold-plated information such as customer lists or financial information but over time, companies have become much better at not leaving spreadsheets lying around the internet.

If you wish to search for information outside the competitor’s website, exclude that website by using the minus operator i.e. “-competitor.com”.

10. TrustRadius (and similar)

A number of websites, such as TrustRadius, provide detailed reviews of software products. To varying degrees, they encourage detailed rather than cursory reviews, and verify the reliability of the person submitting the review.

Such websites are a good source of feature information, and an excellent source of information about customer sentiment, including the features they like and dislike, or the missing features that they wish existed.

Examples: TrustRadius, G2, Capterra, Peerspot, Software Advice, Gartner, Technology Advice.

11. FeaturedCustomers (and similar)

We saw already that sources such as BuiltWith, that provide information about the technology stacks of companies, also provide the customer lists of tech vendors.

Other sources, such as FeaturedCustomers, focus on building these lists primarily by aggregating the customers that competitors list on their websites, or announce in press releases or discuss in other public arenas such as webinars.

Because of how they are created, these lists tend to feature customers that skew towards larger companies, or the competitor considered worth highlighting for some reason. Unlike BuiltWith et al, they are not limited to customers that use the vendor in an external-facing situation (such as their website). So if, for example, Pfizer uses SAP, this likely won’t show up on sites like BuiltWith, because Pfizer’s website code will not have evidence of that, but SAP may have a Pfizer case study, in which case it will show up via a source like FeaturedCustomers.

Examples: FeaturedCustomers, G2.

12. YouTube

It’s always worth searching YouTube for the competitor’s name. Some results will be of limited use, like simple explainer videos, or customer interviews that speak in generic terms of how good the competitor’s product is. But sometimes, you will find that the competitor, or a reseller, has uploaded a more detailed demo of the product, or a webinar with screenshots. Other parties in the competitor’s ecosystem, such as developers or consultants, will also often upload educational videos showing how to use the product.

There are plenty of other sources of information, such as Slideshare, Scribd and others, but the above will give you plenty of competitor data that can be the basis of a solid competitor report.